5 Dinosaur Myths That You Thought Were True

Welcome to a new age of dinosaurs — the age of discovery. In the last 20 years, about three-quarters of all known dinosaur species have been found, and a new species is discovered almost every week. While popular Hollywood movies have given us a simplistic view of these magnificent creatures, the latest scientific research is providing a far different perspective! From their appearance to their speed, find out five myths below that you may have thought were facts!

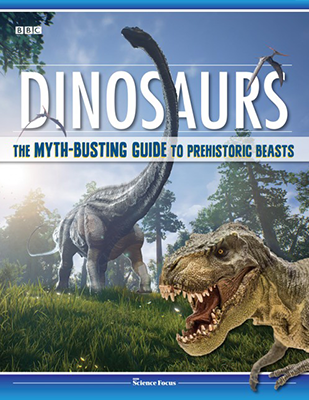

Indeed, dinosaurs are being unearthed at such an incredible rate that I’m half hoping one day I’ll walk out the front door and trip on what looks like a 6 1/2 foot-long Brachiosaurus bone, only to find that I’ve stumbled on a whole new species. (Bennettosaurus does have a nice ring to it.) The wealth of new specimens is keeping paleontologists busy—plenty of fodder for all sorts of new theories about what dinosaurs looked like and how they lived. Dinosaurs: The Myth-Busting Guide to Prehistoric Beasts reports on the latest findings, busting a few dino myths along the way. Journey back in time to discover the key moments in our planet’s history that led to the birth and death of these prehistoric marvels. Find out how they managed to conquer the world, going from being small, furtive animals to a dominant global force. Discover the very latest research on what they looked like. Find out how animals living today are being used to imagine how dinosaurs lived all those millennia ago. Learn about the day the dinosaurs died and what if that ill-fated asteroid hadn’t hit the Yucatan peninsula at that precise time, but had strayed into the deep ocean just a few moments later. And, finally, discover how we could clone a “dinosaur light” version of Velociraptor and build a real Jurassic Park. Immerse yourself in this ultimate guide to the latest research on dinosaurs and prepare to be amazed by the secret lives of these incredible beasts. – Daniel Bennett, Editor of Dinosaurs

Indeed, dinosaurs are being unearthed at such an incredible rate that I’m half hoping one day I’ll walk out the front door and trip on what looks like a 6 1/2 foot-long Brachiosaurus bone, only to find that I’ve stumbled on a whole new species. (Bennettosaurus does have a nice ring to it.) The wealth of new specimens is keeping paleontologists busy—plenty of fodder for all sorts of new theories about what dinosaurs looked like and how they lived. Dinosaurs: The Myth-Busting Guide to Prehistoric Beasts reports on the latest findings, busting a few dino myths along the way. Journey back in time to discover the key moments in our planet’s history that led to the birth and death of these prehistoric marvels. Find out how they managed to conquer the world, going from being small, furtive animals to a dominant global force. Discover the very latest research on what they looked like. Find out how animals living today are being used to imagine how dinosaurs lived all those millennia ago. Learn about the day the dinosaurs died and what if that ill-fated asteroid hadn’t hit the Yucatan peninsula at that precise time, but had strayed into the deep ocean just a few moments later. And, finally, discover how we could clone a “dinosaur light” version of Velociraptor and build a real Jurassic Park. Immerse yourself in this ultimate guide to the latest research on dinosaurs and prepare to be amazed by the secret lives of these incredible beasts. – Daniel Bennett, Editor of Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs

Journey back in time with Dinosaurs to discover the true history behind the birth and death of these prehistoric beasts. Kids 7-14 and adults who are fascinated by dinosaurs will be captivated by the incredible detail and amazing illustrations inside this book! Look beyond the basic, often inaccurate view of these prehistoric animals that’s found in Hollywood movies. In Dinosaurs, you’ll learn all about:

- How they evolved

- What they ate

- How they grew so large

- The mass extinction event that ended their reign

- If it’s really possible to bring them back

- …and much more!

Dinosaurs weren’t just green and black.

Recent Reserach has allowed scientists to unveil the true colors of the Sinosauropteryx. Back in 2010, Sinosauropteryx became the first dinosaur to be illustrated in its true colors. Since then, other feathered dinosaurs, like Archaeopteryx and Microraptor, have had their colors determined too. This extraordinary detective story began with the discovery of fossilized melanosomes. These are the tiny packages of pigment inside feathers and hair in living birds and mammals, and are responsible for making your hair black, brown, blond, or ginger. These melanosomes are incredibly tough, and under the right conditions can survive hundreds of millions of years in fossils. When you look at the feathers of a living bird under a high-powered electron microscope, you can see melanosomes of different shapes. Zebra finches have round “phaeomelanosomes” in the orange part of their feathers and sausage-shaped “eumelanosomes” in the black parts. A team led by Mike Benton at the University of Bristol used this technique to look at the feathers along the head, neck, and back of the fossilized Sinosauropteryx. They found that it was ginger with white stripes down its tail and a dark band around its eyes.

Many dinosaurs were actually covered in feathers.

For continuity, Jurassic World ’s producers stuck with scaly dinosaurs, but the fossil record suggests Velociraptor and many other dinosaurs had feathers. In fact adult T-Rex may have had a down-like feather along its spine. The incredible fossils of nearly 50 species—mostly from China—show a range of feathery coverings, from downy, insulating “dino-fuzz” to flashy display and flight feathers. Some of these animals are so exquisitely preserved that we can see the shape and arrangement of feathers right across their bodies. Sometimes we have other evidence of feathers, such as marks on the forearm bones of Velociraptor, which correlate to the “quill knobs” where the ligaments of flight feathers attach on pigeons today. In the years following the discovery of Sinosauropteryx in 1996, it became clear that most carnivorous theropods wouldn’t have been able to fly—they didn’t have fully formed wings or they weren’t the right kind of shape. Paleontologists began to realize that feathers evolved for another purpose entirely and were only later co-opted for flight. The feathers of many of these animals were simpler in structure than anything we’d recognize as feathers today, and it’s likely they were used like the downy fuzz of chicks for insulation or used to woo mates.

T-Rex was more of a fast-paced walker than a runner.

Contrary to popular belief, Tyrannosaurus could run up to 12 mph – way slower than a car driving at top speed. A Jeep could easily outrun a T. Rex — not even for his lunch. Despite his lack of speed, this “tyrant” lizard was one of the most ferocious predators of all time. With a bite three times stronger than a lion’s, and around 60 saw-edged teeth each measuring up to 8 inches long, T. rex could chomp through bone. It hunted some of the largest and most heavily armored dinosaurs around. But it also scavenged for food—the part of the brain responsible for smell was fairly large, meaning it could sniff out carcasses. Groups of skeletons from close relatives of T. rex have been found, suggesting T. rex might have also hunted in packs. Fossil evidence of bite marks from other tyrannosaurs show they definitely fought one another, competing for food or mates. And there is even some evidence that T. rex indulged in a spot of cannibalism.

Chicken and ostriches show how dinosaurs probably moved.

Many quadrupedal dinosaurs— like sauropods and horned dinosaurs—have limb bones and proportions quite different from those of living animals. Tracks and articulated skeletons give us some indication of how they walked and ran. Based on analogy, it has been proposed that they were similar to elephants, rhinos, or erect-walking crocodylians. But, of Extinct theropods were built much like the birds that are their descendants. Numerous studies have looked at leg structure and movement in ostriches, emus, chickens, and guinea fowl in order to better understand gait and locomotion in the extinct species. But modern birds are different from theropods like T. rex and Velociraptor in having a substantially shortened tail, wider hips, and in doing more of their leg movement at the knee rather than the hip. In an effort to compensate for these differences and better understand locomotion in ancient, long-tailed theropods, Bruno Grossi and colleagues actually raised chickens with a long, tail-like prosthesis attached to their rear ends. These birds learned to walk with a more “dinosaur-like” gait, thus proving that birds still have this ability if aspects of their proportions undergo change.

Hollywood got it wrong about the noises dinosaurs made.

Paleontologists have yet to discover the remains of a dinosaur where the parts of the body associated with noise-making have been preserved. So they use bracketing to make inferences about these structures. Crocodylians and birds possess an organ in the throat called the larynx, so dinosaurs would almost certainly have had one too. Crocodylians generate sound in the larynx while birds have switched to the use of a new structure—the syrinx—located deep inside the chest. What seems likely is that dinosaurs generated sound in the larynx and that the syrinx only evolved in the lineage leading to birds. Can we go further, and use bracketing to predict what sounds dinosaurs made? And can we use analogy to work out how they released sounds into the environment? Crocodylians and giant birds (like cassowaries and emus) make deep, rumbling sounds. These emanate across the environment as the animal exposes and inflates its neck or the front of its chest. The sounds do not emerge from the mouth. In fact, it is kept closed while the sounds are being made. So, the idea beloved of Hollywood—that dinosaurs roared with a wideopen mouth—is highly unlikely.

Get Exclusive Email Offers And Receive 15% OFF On Your First Book Order!

Recent Comments